How were Shakespeare’s works pronounced in his own time? Since the publication, in 1869, of Alexander J. Ellis’s Early English Pronunciation, many attempts have been made to answer this question. But for the past twenty years, one scholar has been especially foremost in the subject: the linguist David Crystal. He has been called “the guiding linguistic spirit” (Johnson 2016:181) behind the movement known as “Original Pronunciation” or “OP,” an attempt to revive in performance the sound-system of Elizabethan English. His work began in 2004, when he served as the linguist for three performances in OP of Romeo and Juliet, staged at the Globe Theatre. A full-scale attempt of this kind had not been attempted since the 1950s (Lodewyck 2013:41). And many more performances in OP have followed, along with books, papers, articles, and, in 2016, the Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation, which offers a pronunciation for every word in Shakespeare, and which Culpepper (2016) calls “one of the most significant works of scholarship to have appeared in recent decades.”

Crystal has founded his reconstruction, above all, on the basis of rhythms, rhymes, and puns, which he refers to as “the best evidence.” Rhymes are particularly favoured by him; which give us the ability, he says, to deduce the value of vowels. (2004:14.). He provides an example of his method when he asks: “How should we pronounce the last syllable of Rosaline—to rhyme with fin or fine?”—“The text makes it clear,” he answers. And then he quotes lines from Romeo and Juliet, in which Rosaline rhymes with mine. And when it seems inappropriate to adapt to either pronunciation in a pair of rhymes, as in the case of haste and fast, he chooses “a pronunciation midway between the two, for both words.”

But there appear to be a number of potential dangers in this way of going about things. The most obvious one is that of uniting the sounds of imperfect rhymes, and mistakenly merging entire lexical sets. Byron, for example, uses many of the same rhymes that Shakespeare does—love with prove, [Sonnet XXXIX/Bride of Abydos, II.X], alone with gone (Sonnet 45/Corsair XIV), forth with worth (Sonnet 38/Mazeppa, VI), and so on. But does it follow that Byron had a similar pronunciation with Shakespeare?

Eye-rhymes, however, says Crystal (2016:xxiv), were generally looked down on in Shakespeare’s day. We infer this from Daniel (rhyme “gives to the ear an echo,”) and read it explicitly in Puttenham (“the good maker will not wrench his word to help his rhyme”). But to this point I would still object, that a good rhyme, for an Elizabethan, may have been phonetically looser than it is for us. And I would also propose two further dangers in Crystal’s method:

First, that a “midway pronunciation,” by which we synthesize words that rhyme, may be mistaken;

And secondly, that the same word may have had multiple pronunciations.

Fortunately, however, we have no need to rely too much on rhymes. For there is a way for us to gain insight into the speech of Shakespeare’s day that is completely independent of them.

In 1569, a revolutionary book was published, entitled: “An Orthographie.” Its author was John Hart, a gentleman who made it his life-work to create an entirely phonological system of English spelling. “Of my treatise,” he says, “the end is one: to use as many letters in our writing, as we do voices or breaths in speaking, and no more; and never to abuse one for another, and to write as we speak.” (1596:6).

The reputation of Hart is very high among linguists. For Dobson (1968:62), “Hart deserves to rank with the greatest English phoneticians and authorities on pronunciation.” For Viereck (2006:220), he is “the best phonetician of the 16th century”; Jesperson (1907:10) calls him “the first phonetician of the modern period”; and Lass (1997:79) refers to his Orthographie as a “masterpiece.”

The system of Hart is profoundly simple. He gives five letters for five vowel sounds, and no more: <a>, <e>, <i>, <o>, and <u>. For the sounds of these vowels, Hart appeals “to all musicians, of what nations soever they be,” (1569:31-33) referring to them also as the vowels of Italian and Spanish. At first blush, then, the letters appear to represent /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, and /u/; although it is also possible that <e> may represent /ɛ/, and that <o> may represent /ɔ/.

It is true that Hart also marks what he calls long vowels with a dot underneath the letter, like this: ạ. But the quality, he assures us, never changes, only the quantity. (Danielsson 1963:40). For an analogy with modern English: “happy” and “receive” have, in the second syllable, the same vowel-sound of /i/. But in “happy,” the sound is short: /hapi/; while in “receive,” the sound is long: /rɪsiːv/. Taking Hart’s system at face value, this difference would be represented by <i> and <ị>.

Now Crystal does make use of Hart; but I do not believe that he makes enough use of him. He refers to writers like Hart as a supplement, instead preferring the chief evidence of spellings and rhymes. (Crystal 2016:xii).[1] But it seems preferable to me that we should use writers like Hart as our chief evidence, and rhymes as a supplement. For then we shall avoid the serious problems that inevitably result from relying on rhymes.

Now Hart contradicts the reconstruction of Crystal in a number of important respects; and I shall go through these one by one.

Words in the price lexical set are, in the OP of Crystal, pronounced /ǝɪ/. Thus for “kind,” “fire,” and “desire,” he has /kǝɪnd/, /fǝɪr/, /dɪzǝɪr/.[2] He takes this /ǝɪ/ sound, presumably, from the works of Kökeritz (1953), Dobson (1968), and Cercignani (1981). But it has been opposed by a number of other linguists, among them Patricia Wolfe (1972) and Roger Lass (1992). They reject it, first, because, in Hart, words in the price lexical set are almost always written with the digraph <ei>; as keind, feiër, dezeir. And secondly, because, from Hart’s descriptions of his letters, we can make no credible interpretation of his letter <e> but a sound of either /ɛ/ or /e/. (See Lass 1992:62, and 82-83; Wolfe 1972:107-8.)

Now to every word in the happy lexical set—the last syllable in words like “lovely” or “city”—Crystal also gives a sound of /ǝɪ/: as /hapǝɪ/ /lɤvlǝɪ/, /sɪtǝɪ/, and so on. This is because words in the price lexical set, and words in the happy lexical set, often rhyme in Shakespeare. Thus Crystal (2011:296) observes that, in Sonnet 154, “by” rhymes with “remedy.” To solve the problem, he provides his /ǝɪ/-sound as a midway pronunciation between the two: /bəɪ/, /remɪdǝɪ/.

But his method of harmonizing rhymes has, in my opinion, led him into a mistake. For we learn from Hart that words in the happy lexical set had alternate pronunciations. Very often, he writes such words with a letter <i>, in accordance with the sound of modern English: “akordingli,” “gladli,” “softli,” and so on;[3] while at other times, he writes them with the digraph <ei>. Thus Hart has both “indifrentli” and “indifrentlei”; “kommonli” and “kommonlei”; “perfektli” and “perfektlei.” So that an Elizabethan, it would seem, could choose to pronounce a word in the happy lexical set, with either /i/ or /ɛi/. The difference between Hart and Crystal can be most strikingly seen in a word like “lively”; which, in Crystal, takes a double-schwa, and is pronounced /lǝɪvlǝɪ/; but in Hart, is given two distinct sounds: leivli.

To anticipate a possible objection. Hart’s letter <e> cannot, I believe, represent a schwa in his digraph <ei>, as Crystal implies in a 2013 blog post. This would defy Hart’s explanations of the letter’s pronunciation: that it is the <e> of Romance languages like Italian and Spanish, or that we sound it by “thrusting the inner part of the tongue to the inner and upper great teeth.” It is true that a single letter <e>, when unstressed, might plausibly be taken to stand, at times, for a schwa. But it is unthinkable that it should do so in a diphthong, leave alone one that appears everywhere in stressed positions.[4]

Another objection may be, that it is unfair to draw conclusions only from Hart. And it is at this point that I wish to introduce another writer into my argument.

In 1621, there was another attempt to make a phonetic system of English, in a book called Logonomia Anglica. The author was Alexander Gil, the master of St Paul’s School, and the teacher of Milton. The attempt was not, says Jesperson (1907:19-21), as faithful as that of Hart; Jesperson going so far as to call it, “simply a reformed spelling, with a leaning towards phoneticism.”[5]

But surely enough, we find that Gil, also, spells words in the happy lexical set in alternate ways. Thus we have mersi (p. 20), beuti (22), piti (141), etc., spelled with a letter <i>.[6] But on the other hand, some are spelled with a letter <j>: thus we have luvlj (123), infamj, uglj, (128), etc. And for greatly, grëtlï (100) and grëtlj (22) show, again, that the same word in this set could take an alternate pronunciation.

What is the value of Gil’s letter <j>? It is not certain. If we are to assign a value to it, then I agree with Wolfe (1972:55), who makes it /ei/; and supposes that, by the graphemes <ei> and <j>, Gil was distinguishing between the sounds /εi/ and /ei/. But what I do, at any rate, observe is, that among dozens of extracts that Gil makes from the poets, <i> and <j> never rhyme. And this circumstance directly contradicts the supposition of Crystal, that words in the happy lexical set always took one sound.

There is another indication that a distinction between <i> and <j> was strongly felt. <i>, for the happy lexical set, is generally pretty common in Gil. But in his extracts from the Bible, such words most frequently take a <j>. It would seem, then, that <j> was felt to represent a more solemn or formal sound than <i>.

Another place where Hart disagrees with the reconstruction of Crystal, is in the choice lexical set, with diphthong /ɔɪ/, as in “voice.” Crystal proposes a schwa for these words also: thus he has /tʃǝɪs/, /vǝɪs/. But Hart spells such words in two different ways. Sometimes, they take the digraph <oi>, as tſois and voises; and sometimes the digraph <ui>, as dʒiuin for join. This distinction is a consequence of their ancestral pronunciations in Middle English. (Lass 1992:102.)

The opinion, then, of Crystal about this line:

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes,

that there is a pun on loins with lines, does not necessarily have foundation. For his reasoning is (2015), that they were both pronounced /ləɪnz/. But from Hart, we infer that they were sounded /luinz/ and /lɛinz/—distinctly, as they are in our own time.

To the strut and goose lexical sets, Crystal generally assigns a sound of /ɤ/. He proposes this sound to make words like “love” and “prove” rhyme, as they do in Shakespeare; thus Crystal has /lɤv/, /prɤv/. But we learn from Hart that such words had the quality, not of /ɤ/, but /u/: for he spells them with a <u>.[7] So in modern English we say goose-words with an /u/, as /pru:v/ or /mu:v/. Gil even distinguishes between “luv” with a short vowel, and “müv” with a long one, similarly to their modern English lengths (128). Furthermore, he even has them rhyme: and this circumstance indicates, that words could rhyme in Elizabethan poetry, even when they differed in quantity. But Crystal, as a result of his method, has lost all quantities in his midway-sound of /ɤ/, by which words like move, prove, and doom, are considerably clipped (/mɤv/, /prɤv/, /dɤm/).

To words in the face lexical set, Crystal ascribes a quality of /ɛ:/, as /fɛ:s/, or, for name, /nɛ:m/. But when they are pronounced with an /a/ in Middle English, Hart and Gil spell such words with a letter <a>, also pronounced /a/. Thus we find, in Hart, for name, make, and places, the spellings nạm, mạk, and plases; and Gil (103) has, mäk, pläs, forsäk (forsake), quäk (quake), etc.

Many sonnets, I find, are more pleasing with Hart as our guide here. In the first quatrain of Sonnet 18, for example, we have the rhyme-words day, temperate, May, and date, which align ABAB. In Crystal, they all have an identical rhyme-vowel of /ɛ:/; whereas if we assume, with Hart, that temperate and date = /tɛmpəra:t/ and /da:t/, then we enjoy a more varied scheme of sound. It is also remarkable that, in the works of Shakespeare, words like hate and state never rhyme with so common a word as great, even though Crystal gives to all of them a sound of /ɛ:/; and it is difficult to conceive that this is a mere coincidence.

To the nurse lexical set, Crystal gives a sound of /ɐ/; as /tɐ:rn/ for turn. But in Hart and Gil, words in this set are written with various vowels: thus Hart has turnd and nurs with a <u>; mersi with an <e>; and Gil has dezart with an <a> (128). There is no evidence in them for any such universal sound as /ɐ/. The merger of words in the nurse lexical set is also said to be a late development in English, only being completed towards the very end of the eighteenth century. (Jones 2006:245).

The sound /ɑ:/ often makes an appearance in Crystal’s dictionary, as in readings like /wɑ:ɹ/ and /dʒɑ:ɹ/ for war and jar. But Hart provides us with no evidence that such a sound existed in his day. For the letter <a>, he provides us with only one possible sound, the /a/ of the Romance languages, which we shape, says Hart (1569:30), “with wide opening the mouth, as when a man yawneth”: /wa:r/, /dʒa:r/.

To the mouth lexical set, Crystal ascribes a sound of /ǝʊ/. But I do not think that a schwa is warranted; for in Hart, such words are spelled with <ou>; thus Hart writes mouþ.

To divert for a moment from comparisons with Hart. Crystal assigns, to the letter r, the West-Country or American sound. But Ben Jonson calls it the dog’s letter, as the nurse in Romeo and Juliet calls “R” “the dog’s name” (II.4.1361-1366); and this much more fittingly describes a rolled R, which is like a snarl.[8] So Aubrey reports, in his Brief Lives, that Milton pronounced the letter R “very hard,” true to its name of littera canina (1949:202). And I do not conceive how a West-Country R can be pronounced hard; whereas a rolled R may be pronounced very hard indeed, as we see in Spanish. Samuel Johnson, writing at so late a date as 1755 (Grammar of the English Tongue), describes the letter R as rolled, and in significant language: “R,” he writes, “has the same rough, snarling sound as in other tongues.” [My italics.] But perhaps the most important evidence on this matter is that, when the R is rolled, many lines in Shakespeare gain an appropriately harsh effect, as these ones in Lear:

“Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes,” &c. (Act III, Scene 2, 1678-1700).[9]

I am sceptical of the claim of Crystal and others, that we must often drop the letter <h> to be authentically Elizabethan. Undoubtedly, some speakers did often drop it; but both Hart and Gil consistently write the <h>, and this is a choice that surely ought to be respected. They do not merely write <h> for the sake of spelling, for they leave it unwritten in words like honour or hour. That <h> was dropped, however, in words like unstressed him or her, I can well believe; both by analogy with modern English, and from the spelling of words like dungell for dunghill, where an unstressed <h> is lost (Crystal 2016:xxix).

Contrariwise, an h-sound is often warranted, at least as an option, where it is missing in Crystal’s dictionary. The digraph <gh> often takes a letter <h> in the transcripts of Hart; and without this aspirate, Shakespeare is at times less effective. A phrase like “rough winds,” for example, is more pleasing when the <gh> digraph is sounded, since it is a sort of onomatopoeia—/rʊh wɛindz/.

Enough has now been said to show that the system of Crystal ought to be re-evaluated. His work on OP is highly innovative and commendable. But to use spellings and rhymes as our chief source of information, with the phoneticians merely as a supplement, is surely to put the cart before the horse. John Hart, in particular, dedicated his life to creating an accurate record of the pronunciation of his time; and we must not attempt a reconstruction that does not take him into the most serious consideration.

What alternative, then, would I advocate for? It would lie outside either the scope of this essay, or my own poor knowledge of linguistics, to provide anything like an alternative to Crystal’s dictionary. But it may still be of use to give an overview of my own preferences for performing Shakespeare in reconstruction, which others are at liberty to take or leave as they see fit.

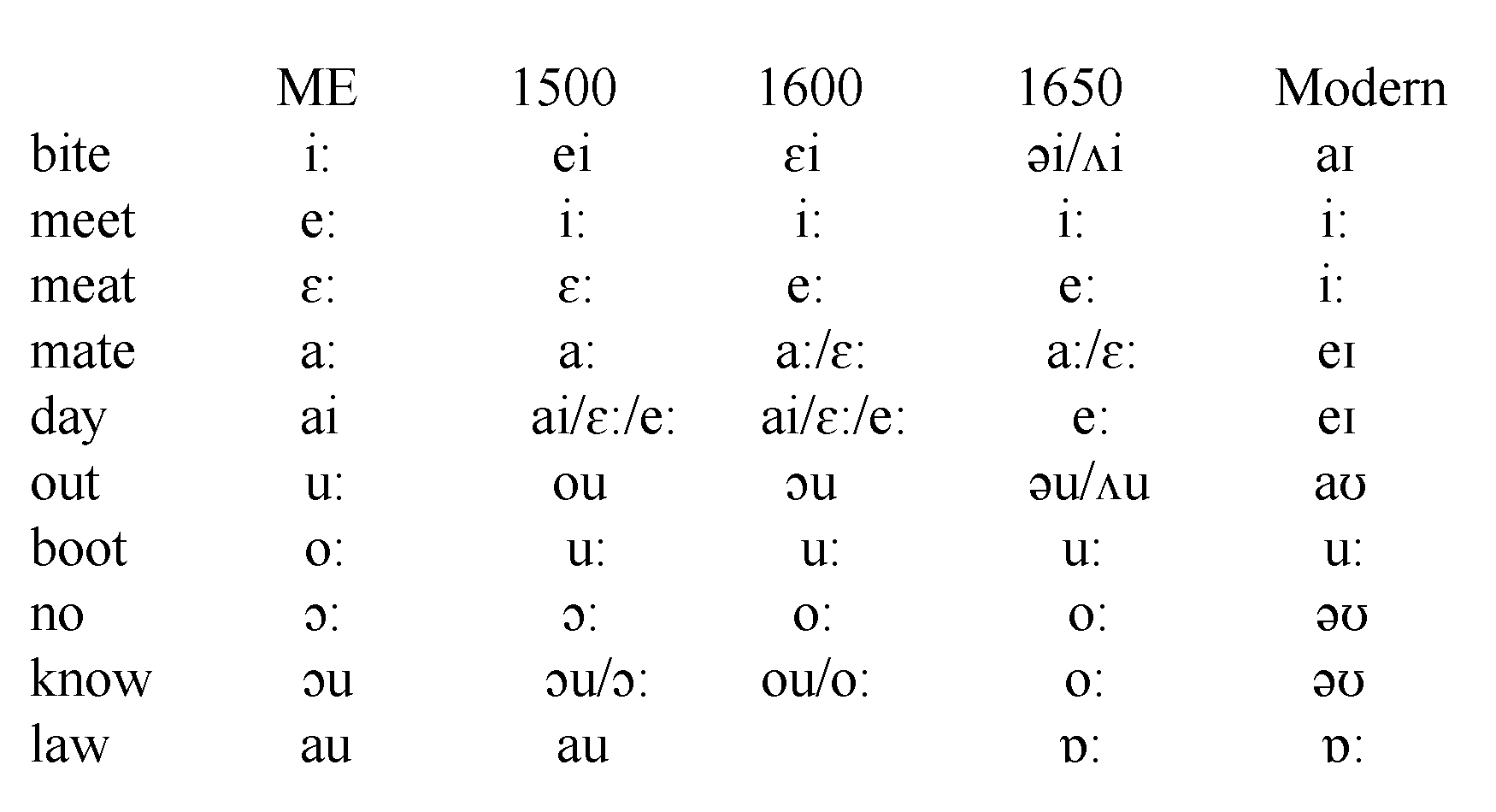

The first point to consider, is that any reconstruction must take some account of the Great Vowel Shift. In 1909, Otto Jesperson first identified this famous phenomenon. It is the process by which the long vowels of Middle English became the long vowels of our modern tongue. Thus Chaucer said /bi:t/, and we say bite; he said /me:t/, and we say meet; he said /dai/, and we say day, and so on. To find the long vowel-sounds in the time of Shakespeare, then, we must deduce at what stage the Great Vowel Shift then generally was.

The scholar who, in my opinion, has given the best account of the Great Vowel Shift is Roger Lass. This is because he bases his account on a deep respect for the work of the Elizabethan phoneticians, especially John Hart, whom he calls “perhaps the most important phonetic source for [his] period.” (2008:82.) The following is an overview of Lass’s reconstruction. My sources are “Phonology and Morphology,” in the third volume of The Cambridge History of the English Language, and in A History of the English Language, edited by Hogg and Denison.

In practice, of course, pronunciation was not so neatly arranged as this. Some speakers may have used a more advanced, and some a less advanced, pronunciation, for various words in each category. But the chart does at least provide us with the ability to make a historically-informed approximation. Whether we use a pronunciation closer to 1500, 1600, or even 1650, depends on our taste; my own preference, generally, is to use the sounds from 1600.[10]

It will be seen that /əɪ/-sound of Crystal’s system does eventually make an appearance in 1650. According to Lass, /ɛi/ first developed into /əi/, and then into /ʌi/. That /əi/ developed into /ʌi/ appears to be generally accepted by linguists; although Wyld (1920:225) is a dissenting voice, who thinks that /ɛi/ developed straight into /ʌi/.

Over and above a general overview of the Great Vowel Shift, the Elizabethan phoneticians also offer us great insight. They teach us the pronunciation of many words. They show us variant pronunciations, as that the word my could be pronounced both /mi/ and /mɛi/, weakly or strongly. And they reveal more advanced pronunciations, which we may take or leave at our pleasure. Thus even though the transition from mɛ:t to mi:t was not complete even by 1650, we find in Hart readings like apịr, klịn, and rịd.

In this essay, I have spoken exclusively about Hart and Gil as phonetic writers. But there are, of course, many other writers to be learned from also. For words ending in -tion and -sion, for example, Hart and Gil, where we pronounce /ʃən/, write <sion>, implying a hiss. But we may prefer to follow the more advanced pronunciation of their contemporary Mulcaster, who in such cases writes <shon>. (Lass 2008:93). And Shakespeare himself, as Crystal (2005:75) points out, has lushious for luscious, and marshall for martial. Palatalization in words like vision, on the other hand, which class of words Hart spells with a <z>, would seem to be an even more advanced development; the earliest unambiguous evidence for which appears in Richard Hodges, writing in 1644, who refers to our /ʒ/ as zhee. (Lass 1992:121.)

Lass provides multiple possibilities for pronouncing words like day. An overview of the situation is as follows:

For words like day, play, sail, etc., which in Middle English were pronounced /ai/, Hart writes a long letter <e>: as dẹ, plẹ. Jesperson (1907:33) was the first to point out the trouble in this. For Hart also writes a long letter <e> in words like sea and seal. Now words like say and sea, sail and seal, are distinctly sounded in both middle and modern English. So that, if Hart’s long <e> was the standard pronunciation, then how did these categories begin separately in sound, then coalesce, and then separate again?

The solution proposed by Wolfe (1972:35) is that Hart’s long <e> in words like day was dialectical. She bases this on a complaint of Alexander Gil, that Hart’s transcription with a letter <e> in words like day is a feature of what Gil calls “the Mopsey dialect.” In agreement with Middle English, Gil always writes such words as <ai>. The conclusion to all this is that we have a choice in our pronunciation of words like day. My own preference is to follow Gil, and say /dai/, both for historical and aesthetic reasons; but others may prefer to follow Hart, and say /de:/ or /dɛ:/.

Lass also gives us a choice of saying words like mate as either /ma:t/ or (as in Crystal) /mɛ:t/. But as Hart, Gil, and the rhymes of Shakespeare all support, for words that were pronounced /a:/ in Middle English, a reading of /a:/, I prefer /ma:t/. And according to Lass (1992:84): “ME /a:/ shows some raising in the sixteenth century, but is not stable at /ɛ:/ until well into the seventeenth.” [My italics.]

There are a couple of points where I disagree with Lass. My first disagreement is with his belief that the short vowels /ɪ/ and /ʊ/ did not yet exist in Shakespeare’s day. Thus in his opinion, words like did and book were pronounced, not /dɪd/ and /bʊk/, but /did/ and /buk/. (Lass 2008:84). His point of view, as he says, is not a widely-held one. The usual view is that they existed even in Middle English times. But he bases it on the explicit statement of John Hart, that the vowels in his system are, qualitatively, the same. Thus if Hart writes did, then must we not pronounce /did/?

My answer to this is, that Hart appears to have had a slightly looser definition of quality than we do. For Lass (2008:62) interprets the five vowel-letters of Hart as having the following qualities:

/a/, /ɛ/, /i/, /ɔ/, /u/.

And yet Hart also uses his letters <e> and <o> to represent words that have the sounds, not of /ɛ/ and /ɔ/, but /e/ and /o/. Indeed, he even goes so far as to say, that every one of the vowel-sounds in his system can be found in the Italian word riputazione (modern Italian: /ri.pu.tatˈt͡sjo.ne/). Nor does Hart show any acknowledgement of the fact that the Italian letters <e> and <o> have, each of them, two sounds: that letter <e> may be either /ɛ/ or /e/, and that letter <o> may be either /ɔ/ or /o/. The distinction did exist in the Italian of his time; for in 1524, the scholar Trissino had tried to reform Italian spelling, by introducing, for the sounds /ε/ and /ɔ/, the letters <ε> and <ω>.

It follows, then, that Hart, who was writing in the infancy of phonetics, could use one letter to represent what we now regard as two different qualities, which he perceived to be the same. And if he was happy to use his letters <e> and <o> to signify both /ɛ/ and /e/, /ɔ/ and /o/, then why should we forbid that his letters <i> and <u> could also represent /ɪ/ and /ʊ/? Indeed, even when we look forward as far as the eighteenth century, we find Benjamin Franklin, in his phonetic alphabet, using only one symbol for the vowel of both did and deed. (Krapp 1925:187.)

Thus the Elizabethan short vowels are, in my opinion, /a/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /ɔ/, and /ʊ/. Short /ɔ/ would eventually lower to /ɒ/ before voiceless fricatives, as in off or cloth; /a/ would eventually change to /æ/; and the sound /ʌ/ would be introduced. But these particular changes were not stabilized until the mid-seventeenth century. (Lass 2008:84-86).

I also disagree with Lass on the pronunciation of the schwa. Hickey (2010:5), summarizing the position of Lass, says that he sees “little evidence for the existence of schwa before the late modern period.” But Joan Beal, adds Hickey, is more cautious. “She points out that the prescriptivists refer to what is later schwa as an “obscure u-vowel,” which suggests that it was indeed already a schwa in the eighteenth century.” And Hickey goes on to write: “Spelling variations, and not least the loss of inflectional syllables already in the early Middle English period, would seem to indicate that short unstressed vowels have had a centralized pronunciation in English for something like a thousand years.”

Hart also provides us with evidence that the schwa was pronounced in his time. He appears to signify the sound of the schwa by omitting a letter: thus he writes oftn, ivn, artikl, litl, givn, hapn, remembr, etc. Sometimes, the same word will be written both with a vowel in the schwa-position and without one: thus we have, for water, both uạtr and uạter, and, for labour, both lạbr and lạbur. And this variance indicates to me that any unstressed vowel stood for a potential schwa, even when written out in full.[11]

Such are my minor disagreements with Lass. But my preference, upon the whole, would be to reconstruct the speech of Shakespeare’s time according to the account of the Great Vowel Shift given in him, with reference to the Elizabethan phoneticians for additional insight.

I will conclude by making one last point, about the limitations of the OP project itself with respect to authenticity. One danger of performing in a reconstructed pronunciation, is that an actor is liable to sacrifice sense for sound. He or she is easily led to concentrate, not on the meaning of the text, but on the mere enunciation of its words. Performance in OP has an important place, and has the ability to give fresh insight into Shakespeare. But we should not lose sight of the fact that the best way to shed light on Shakespeare, is a meaningful delivery of his language. The eternal performances of Garrick and Barry, Kean and Siddons, were spoken in the pronunciation, not of another time, but their own time; and the greatest accomplishment for an actor of Shakespeare is, not the reproduction of certain vowels and consonants, but intelligent interpretation and passion.

–

I wrote this essay in an attempt to find a reconstruction of 17th-century speech that was both aesthetically pleasing to me and plausible for Shakespeare’s time. I hope that it may be of some use to people who are looking for an overview of Elizabethan pronunciation, and or for an alternative to Original Pronunciation. I have no training in linguistics, and I apologize for any faults on that account.

Published on the 25th of December, 2022; last edited 09 January 2023.

–

[1] “For the Elizabethan period, chief among [the data to reconstruct the sound system] are spellings and rhymes, which—judiciously interpreted, and supplemented by the observations of contemporary writers on language—provide most of the information we need in order to reconstruct OP.”

[2] All citations from Crystal are from his 2016 dictionary.

[3] All citations from Hart are in Jesperson’s word-list (1907:65).

[4] Speaking of the eye/symmetry rhyme in Blake’s Tyger Tyger, Crystal writes: “John Hart, writing in the 1570s, transcribes boldly as boldlei, certainly as sertenlei, and so on… In my work on Shakespearean Original Pronunciation, I transcribe this as a schwa + i… Blake is recalling an earlier pronunciation… by the time [he] was writing, the everyday pronunciation had shifted to its modern form, like a short ‘ee’.”—But what of Hart’s many spellings like brịfli, gladli, triuli, and so on, which also concern this lexical set? A solitary letter <i>, Hart tells us, is to be sounded like the /i/ of the Romance languages, in other words with what Crystal calls the “short ee” of our modern pronunciation.

[5] “Unlike Hart, Gil gives no articulatory description of the vowels.” (Wolfe 1972:51-52)

[6] All citations are from Gil 1621.

[7] This statement is, however, to be qualified by what I say later about the Elizabethan short vowels.

[8] In his dictionary, Crystal (2016:XLVI) allows that Jonson may be referring to a trilled R; but, if I understand him correctly, only when the R comes in front of a vowel, and even then as a “variant.” I have not, at any rate, been able to discover an OP production where the R is trilled. Jonson’s statement that R is “sounded firm in the beginning of the words, and more liquid in the middle and ends,” I interpret as signifying a trill in an initial position, and otherwise a tap. I say a tap, and not an approximant, in part because countless lines in Shakespeare lose much of their beauty and power when the R is unrolled, even in the middle and at the end of words. Compare, for example, the wonderfully harsh effect produced by the line from Henry V, cited in the next footnote, only one of whose five Rs is initial.

[9] Other examples where the R is more appropriately rolled are these lines in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which are said to belong to “a part to tear a cat in, to make all split”:

The raging rocks

And shivering shocks

Shall break the locks

Of prison gates (I.2.285-294);

this onomatopoeic line in Henry V, as indicated by the phrase “hard-favoured rage,” hard-favoured meaning coarse- or rough-featured:

Disguise fair nature with hard-favoured rage (III.1.1092);

and Antony’s words in Julius Caesar, on the violent power of ingratitude:

Ingratitude, more strong than traitors’ arms (III.2.1714).

[10] Words like mate, says Lass, developed into /ɛ:/ by means of /æ:/, so that a pronunciation of /æ:/ is also possible; the same is true of /æi/ with respect to words like day. /a:/ and /ai/, however, would be the conservative choices. With respect to words like law, Lass (1992:94) says: “The diphthong [au] remains through the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (Hart, Gil)”; (nb., this statement implies, I presume, that diphthongal and monophthongal pronunciations co-existed); “Robinson (1619),” continues Lass, “seems to be the first to show consistent monophthongisation, though he is rather advanced. By the 1650s monophthongisation is general.”

[11] Has Lass (1992:133) overlooked this circumstance? He writes, “Early writers like Hart … make no mention of special qualities in weak syllables,” a statement which is accepted by Beale (2014:150). Technically speaking, this is true; but Hart’s dropping of letters where we pronounce a schwa, is at least, I should think, worth acknowledging. True, it does not absolutely contradict one possibility that Lass proposes, that “There was no single phonetic /ə/ in earlier times, but rather a set of centralised vowels in weak positions, whose qualities were reminiscent of certain stressed vowels, and could be identified as weak allophones without explicit comment.” But if this was the case, first, why does Hart choose to omit vowel-letters at all, since this would obscure a connection with the corresponding vowel in the centralized set? And secondly, would not Hart’s making no explicit mention of many different centralized qualities, as opposed to a single quality, amount to an even greater “defect of analysis” (to quote Lass) that one would be “disinclined to believe,” given his “general acuity”?

–

Works cited

Aubrey, J. (1949), Brief Lives, ed. by O. L. Dick, London: Secker and Warburg.

Beal, J. C. (2014), English in Modern Times, 1700-1945, Abingdon: Routledge.

Cercignani, F. (1981), Shakespeare’s Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Crystal, D. (2004), “Saying It as It Was,” in Around the Globe, 27, pp. 14-15.

Crystal, D. (2005), Pronouncing Shakespeare: The Globe Experiment, Cambridge.

Crystal, D. (2011), “Sounding out Shakespeare: sonnet rhymes in original pronunciation,” in Vera Vasic (ed.), Jezik u Upotrebi: Primenjena Lingvistikja u Cast Ranku Bugarskom, pp. 295-306.

Crystal, D. (2013), On a burning poetic question, Available at: http://david-crystal.blogspot.com/2013/09/on-burning-poetic-question.html (Accessed: 25 December 2022).

Crystal, D. (2015), Pronouncing English as Shakespeare Did, Available at: https://www.folger.edu/shakespeare-unlimited/original-pronunciation (Accessed: 25 December 2022).

Crystal, D. (2016), The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Culpeper, J. (2016), “David Crystal, Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation,” Spenser Review 47.1.6 (Winter 2017). Available at: http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/spenseronline/review/item/47.1.6 (Accessed 25 December 2022).

Danielsson B. (1963), John Hart’s works on English orthography and pronunciation [1551, 1569, 1570], part II: Phonology, Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell.

Dobson , E. J. (1968), English Pronunciation 1500–1700, Volume 2: Phonology, 2nd edition, Oxford: Clarendon.

Gil, A. (1621), Logonomia Anglica, second edition, London: Iohannis Beale.

Hart, J. (1569), An Orthographie, London.

Hickey, R. (2010), “Attitudes and concerns in eighteenth-century English,” in Eighteenth-Century English: Ideology and Change, ed. by Raymond Hickey, pp. 1-21, Cambridge.

Jesperson, O. (1907), John Hart’s Pronunciation of English, Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung.

Johnson, K. (2016), The History of Early English, New York: Routledge.

Johnson, S. (1755), A Dictionary of the English Language, Vol. 1, London.

Jones, C. (2006), English Pronunciation in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kökeritz, H. (1953), Shakespeare’s Pronunciation, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Krapp, G. P. (1925), The English Language in America, Vol. 2, New York: Century.

Lass, R. (1992), “Phonology and Morphology,” in The Cambridge History of the English Language, Vol. III, ed. by R. Lass, pp. 56-186, Cambridge.

Lass, R. (1997), Historical Linguistics and Language Change, Cambridge.

Lass, R. (2008), “Phonology and Morphology,” in A History of the English Language, ed. by R. M. Hogg and D. Denison, pp. 43-108, Cambridge.

Lodewyck, L. A. (2013), ““Look with Thine Ears”: Puns, Wordplay, and Original Pronunciation in Performance””, in Shakespeare Bulletin, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 41-61.

Viereck, W. (2006), “John Hart,” in The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd edition), ed. by K. Brown, Oxford: Elsevier.

Wolfe, P. M. (1972), Linguistic Change and the Great Vowel Shift in English, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wyld, H. C. (1920), A History of Modern Colloquial English, Oxford: Blackwell.